Welcome to earningsHub PRO, the premium edition for TMT professionals seeking clear and independent analysis of the financial moves shaping the digital economy.

In this issue:

Cable is not losing the U.S. connectivity war. It is changing the battlefield.

The new KPI is not broadband net adds. It is relationship durability.

Fixed wireless is now a real broadband growth engine, not a side product.

Convergence has become the CFO’s most valuable retention lever.

In case you missed it:

The broadband story used to be easy. Add lines, beat your rival, print a clean net-add chart, and watch the market reward scale. That scoreboard is now evolving.

In the latest U.S. earnings cycle, the industry delivered a clean and uncomfortable signal: broadband is no longer a growth trophy. It is a relationship anchor.

The winners are not the operators adding the most broadband lines. The winners are the operators converting connectivity into a multi-product household that is harder to churn.

That is the Broadband Reset. And it is already visible in the numbers.

The new scoreboard: Relationship Economics

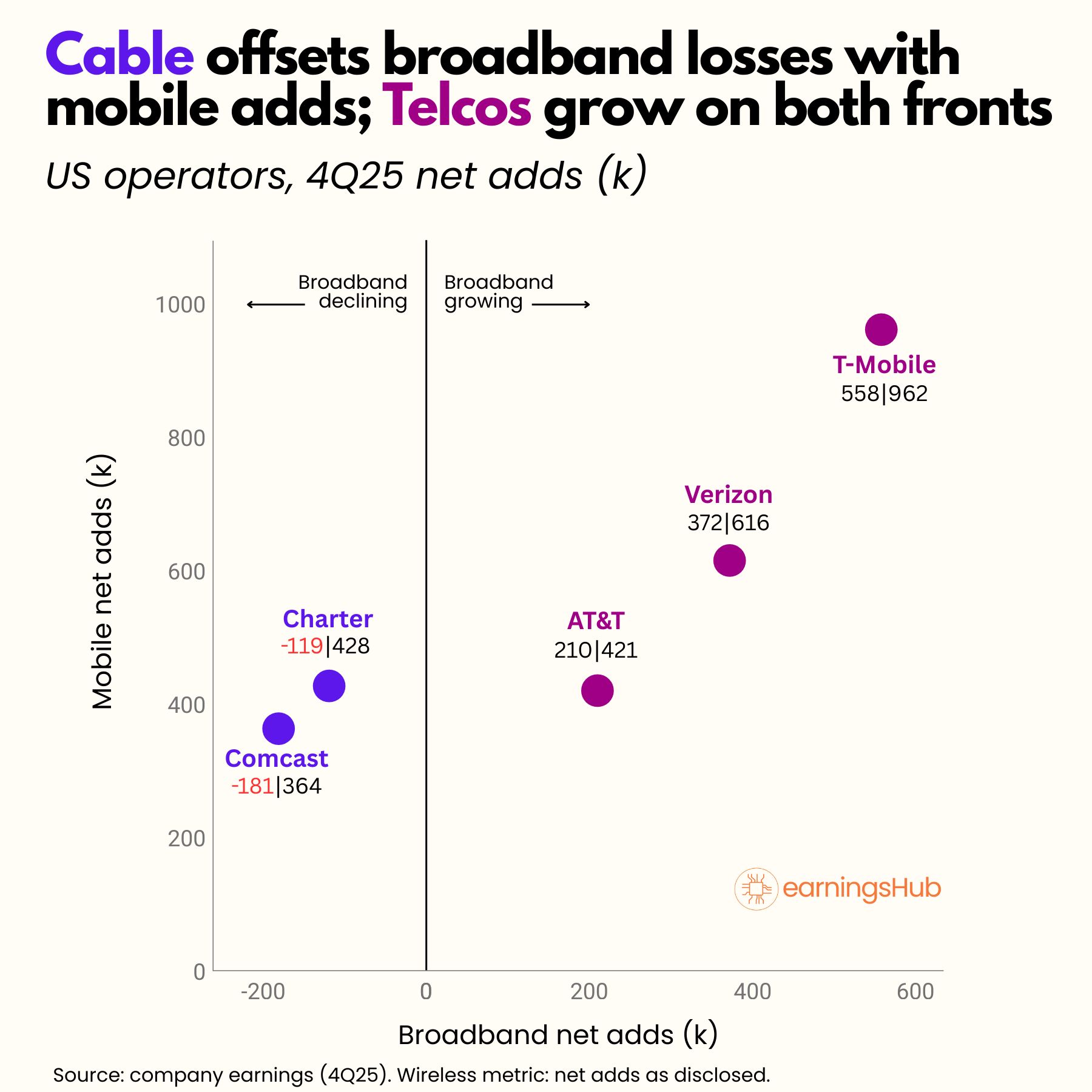

The U.S. connectivity market is splitting into two realities. Cable operators are showing broadband losses. Telcos are showing broadband gains.

But the deeper story is not who is winning broadband share. The story is who is building the stickiest household relationship.

In Q425, Comcast $CMCSA ( ▲ 0.16% ) reported -181k domestic broadband customer net losses and Charter $CHTR ( ▲ 0.9% ) reported -119k total internet customer net losses.

Meanwhile, telcos posted strong broadband growth: AT&T $T ( ▼ 2.79% ) reported +210k broadband net adds, Verizon $VZ ( ▼ 1.8% ) reported +372k broadband net adds, and T-Mobile $TMUS ( ▼ 2.9% ) reported +558k total broadband net customer additions.

That sounds like a clear “telcos are winning broadband” narrative. It is not wrong, but it is incomplete.

Because in the same quarter, cable did not behave like a business retreating from connectivity. It behaved like a business reallocating growth into a different layer of the relationship.

Comcast posted +364k domestic wireless line net additions, and Charter posted +428k mobile line net additions.

Cable is losing broadband customers. But is gaining wireless lines. That is not random. That is the strategy.

Broadband has shifted from being the “product you sell” into the “relationship you defend.”

The Household Lock-In Stack: the layered set of connectivity products (broadband + mobile + WiFi + service continuity features) that increases switching friction, reduces churn probability, and stabilizes unit economics at the account level.

In the old model, broadband was the core product. Everything else was incremental. In the new model, broadband is the anchor product. Wireless is the retention layer. And “always-on connectivity” features are the glue.

The Lock-In Stack turns the household into a system, not a subscription. This is why net adds are losing predictive power.

A household can churn broadband while still being monetized through mobile. Or it can stay broadband stable because mobile attachment increases switching costs.

The unit of competition is no longer the broadband line. It is the household relationship.

“Churn Insurance” is now earnings call language

The most important shift in this earnings cycle was not a promotional offer. It was a disclosure.

Charter put the convergence logic into SEC-filed language: “Bundling reduces churn, reduces service transactions per relationship, lowers the cost to acquire and serve customers, and improves profitability.”

That is not positioning. That is the business model described as causality. It is a formal articulation of the convergence thesis: bundling is not about selling more products. It is about reducing churn, reducing service friction, and protecting margin.

And it lands differently when you place it against the quarter’s hard customer flow math described in the chart above.

Cable broadband was negative. Comcast lost -181k domestic broadband customers. Charter lost -119k internet customers. Yet both operators posted meaningful wireless line growth.

Wireless is not being built as a separate growth vertical. It is being built as the retention layer that keeps the broadband relationship from breaking.

This is why “churn insurance” fits as a financial framing. Insurance is not free. It requires a premium.

In convergence, the premium comes in the form of discounts, device subsidies, promotional complexity, and operational integration costs. It shows up in offer design, in marketing spend, and in customer support load. It is real cost.

But what operators are buying with that premium is not just incremental revenue. They are buying lower churn probability, longer customer life, and higher lifetime value.

The most important point is that this is not theoretical.

AT&T disclosed that 42% of AT&T Fiber households also choose AT&T for wireless. That is a direct measure of convergence penetration. And it is an early indicator of where churn risk is being redistributed: away from standalone broadband and into the relationship portfolio.

Verizon and T-Mobile are reinforcing the same lens through the metrics they highlight. Both disclose ARPA (revenue per account), and both disclose postpaid phone churn. These are relationship-level constructs. They are not designed to explain “how many lines did you add.” They are designed to explain “how stable is the cash engine per account.”

Even the broadband growth story itself has changed shape.

Verizon’s +372k broadband net adds were largely driven by +319k fixed wireless access net adds. T-Mobile’s +558k broadband net customer additions were driven by +495k 5G broadband net adds. The market’s incremental broadband growth is increasingly wireless-led.

That matters because it compresses the margin for error in the cable model.

Broadband is no longer defended only by network advantage. It is defended by relationship depth.

The strategic implication is blunt: if broadband is easier to churn, operators must make the household harder to leave.

The CFO takeaway: convergence is a margin instrument

In the net-add era, broadband was managed like a unit growth product. Add customers, scale fixed costs, expand margin.

In the churn insurance era, broadband is managed like a retention asset. The question becomes: what is the cheapest way to keep the relationship alive and monetizable?

That is why convergence is no longer a marketing slogan. It is a financial instrument.

Charter’s language makes that explicit. Lower churn reduces revenue volatility. Fewer service transactions reduce opex. Lower cost to acquire and serve improves contribution margin. Profitability becomes more stable even if broadband adds are negative.

And once convergence becomes a margin instrument, the metrics that matter shift naturally:

From broadband net adds

To churn stability, ARPA durability, and relationship penetration

That is why companies are changing how they report customers. Because when the business model changes, the accounting story has to change with it.

Broadband is not dead. But it is no longer the hero. It is the anchor. And in 2026, the anchor is what keeps the whole household P&L from drifting.

Keep the signal going

If this issue sharpened how you think about broadband, it will probably sharpen someone else’s too.

Forward it to one colleague who’s tracking broadband and wants a clearer read on where the market is heading.

If you want more of the thinking behind our charts, subscribe to earningsHub FREE. It’s where we break down the logic of decision-grade visuals, one chart at a time.

And if you want to keep the conversation going, follow us on LinkedIn.

Looking for more timely, independent, thesis-driven analysis of the financial moves shaping the digital economy?

earningsHub PRO is where we turn signals into a clear point of view, with decision-grade intelligence you can use in your own conversations.

Upgrade to keep receiving earningsHub PRO

Disclaimers

The information in this newsletter is for general informational purposes only. earningsHub provides financial analysis based on publicly available information from sources such as SEC filings, conference call transcripts, and company press releases. Our content does not constitute financial advice or recommendations to buy or sell securities. Investing in securities involves risk, and past performance is not indicative of future results. We make no guarantees about the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information presented here. We are not liable for any errors or omissions in our content or for actions taken based on it. Readers should conduct independent research and consult with financial professionals before making investment decisions. By using this newsletter, you agree to these terms. This disclaimer may change without notice.

.